Youth who receive special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) and especially young adults of transition age, should be involved in planning for life after high school as early as possible and no later than age 16. Transition services should stem from the individual youth’s needs and strengths, ensuring that planning takes into account his or her interests, preferences, and desires for the future.

Risk and Protective Factors

The previous section on the prevalence of opportunity youth highlighted that certain groups of youth and young adults face a greater risk of becoming disconnected from work and school. This section explores why some groups are more vulnerable than others and more likely to become disconnected (risk factors), while also looking at the relationships and opportunities that can increase connection (protective factors).

Understanding the risk and protective factors associated with youth disconnecting from work and school can be helpful when working with opportunity youth. This information can be used to incorporate protective factors into programming or decision-making, while minimizing risk factors as best as possible and where it is appropriate.

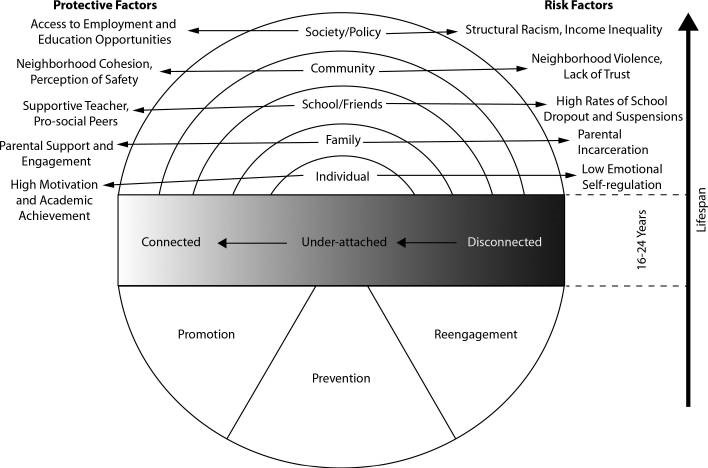

The Conceptual Model of Youth Connection and Disconnection (Figure 2) is a theoretical framework used to show underlying factors that can lead to youth disconnecting from their family, school, friends, community, and society.

Figure 2. Conceptual Model of Youth Connection and Disconnection.

Image Source: Mendelson et al., 2018

This model is based on the Positive Youth Development Framework “which views youth development as embedded within family, school, community, society, culture, and history, and which promotes strategies that provide opportunities that build on young people’s strengths.”[1] A key idea behind this model is that youth have the capacity to positively change and adapt during this time of rapid physical, emotional, and cognitive change.[2] This model also emphasizes that “promotion of connection, prevention of disconnection, and reengagement of disconnected youth” can be used for all youth and young adults, to identify and support some youth and young adults with risk factors, and with those showing signs of disconnection.

Protective Factors

While there is no single factor that can protect an individual from becoming disconnected there are several factors that research suggests can help youth to maintain and strengthen connections.[3] These findings can be used to develop and implement evidence-based approaches for working with opportunity youth. These factors also fit within the Conceptual Model of Youth Connection and Disconnection and include:

- Opportunities & Training. Youth who have access to more employment and educational opportunities are less likely to become opportunity youth. Additionally, youth who have access to job skills and educational training are more likely to stay connected.

- Environment. Research suggests that youth who live in areas that they perceive as safe and consistent are more likely to stay connected with their communities.

- Support Systems. Youth who have support and engagement from educators, peers, and parents are much less likely to become opportunity youth.

- Internal Factors. Individuals who are highly motivated, have good emotional regulation, and are higher achieving students are less likely to become opportunity youth.[4] Emerging brain science underscores that these social and emotional mindsets and skills are learned, and can be fostered or hindered in learning and community environments, and by experiences with trauma and stress.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for youth disconnection can vary by environment and developmental stage, however main risk factors for opportunity youth have been identified through research.[5] Several risk factors are shown in Figure 2, such as low emotional self-regulation, parental incarceration, and neighborhood violence. Other risk factors include:

- placement in child welfare

- missing numerous school days

- associating with deviant peers

- family trauma and experiences of trauma

- parental unemployment

- not graduating high school/dropping out of school

- experiencing discrimination at school or workplace[6]

Strategies for Preventing and Reducing Youth Disconnection

Prevention and reduction approaches used with opportunity youth, or those at risk for becoming opportunity youth, utilize strategies to reduce risk factors and elevate or strengthen protective factors. Prevention strategies should be implemented at multiple environmental levels (e.g., school, family, community) during different developmental stages. Additionally, research has shown that prevention strategies should include:

- strengthening connections within the main areas of young people’s lives (school, family, and community), and

- promoting academic and career engagement among young people.[7]

The most common reduction approach is to use reengagement strategies to reconnect or strengthen youth and young adults’ connection to their school, community, and employment opportunities. Examples of reengagement strategies include:

- engaging in environmental or national service projects,

- workplace readiness training, and

- life skills training.[8]

A common thread across these strategies is the concept of developmental relationships. These are relationships that “help young people forge identities, learn new skills, and strengthen the roots of their success. Family members, teachers, school administrators, coaches, program leaders, and others can help young people figure out who they are and who they can become.”[9] The five main points of the developmental relationship framework includes:

- Express Care: Show me that I matter to you.

- Challenge Growth: Push me to keep getting better.

- Provide Support: Help me complete tasks and achieve goals.

- Share Power: Treat me with respect and give me a say.

- Expand Possibilities: Connect me with people and places that broaden my world.[10]

Developmental relationships can help young people to feel connected to their family, school, and community. While the COVID-19 pandemic has placed extra strain on the ability to support youth, there are ways to continue building developmental relationships while young people are at home.

Lastly, it is crucial to assess for and acknowledge opportunity youths’ ability to travel to school and work opportunities. One of the more prominent barriers for opportunity youth is lack of accessible and affordable transportation. Another key barrier that has emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic is access to reliable Internet for school and work opportunities, and accessing services. This prevents many opportunity youth from being able to reliably get to school, workplaces, job training centers, and career and technical education programs.[11] This barrier should be considered when developing and implementing programming for opportunity youth, including providing direct transportation and/or providing financial resources to cover transportation costs such as smart metro cards, train passes, etc.

Resources

Building Developmental Relationships During the COVID-19 Crisis (PDF, 2 pages)

This checklist from the Search Institute presents relationship-building steps that can be taken by school and youth program staff to stay meaningfully connected to students during COVID-19.

Promising Gains, Persistent Gaps: Youth Disconnection in America

This report from the Social Science Research Council, details demographic information about opportunity youth. This data was collected as a part of the Measure of America study, looking at the breakdown of opportunity youth by region, gender, and race.

Making the Connection: Transportation and Youth Disconnection (PDF, 39 pages)

This document from the Measure of America consists of a detailed breakdown of opportunity youth by region, race, ethnicity, and gender along with outlining issues, trends, and consequences of the opportunity youth experience.

What Works for Disconnected Young People: A Scan of the Evidence (PDF, 57 pages)

This working paper from MDRC presents and discusses a scan of the state of the evidence regarding what works in helping disconnected young people, defined as the population of young people ages 16 to 24 who are not connected to work or school.

References

[1] Lerner, Lerner, Almerigi, Theokas, Phelps, Gestsdottir,…von Eye, 2005; Taylor, Oberle, Durlak, & Weissberg, 2017

[3] Burd-Sharps & Lewis, 2017; Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018; Lewis, 2019

[4] Burd-Sharps & Lewis, 2017; Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018; Lewis, 2019

[5] Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018; Lewis, 2019

[6] Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018; Lewis, 2019

[7] Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018

[8] Mendelson, Mmari, Blum, Catalano, & Brindis, 2018

[9] Search Institute, 2020a

[10] Search Institute, 2020b

[11] Lewis, 2019

Other Resources on this Topic

Announcements

Collaboration Profiles

Feature Articles

Publications

Resources

Webinars & Presentations

Youth Topics

Youth Briefs

Research links early leadership with increased self-efficacy and suggests that leadership can help youth to develop decision making and interpersonal skills that support successes in the workforce and adulthood. In addition, young leaders tend to be more involved in their communities, and have lower dropout rates than their peers. Youth leaders also show considerable benefits for their communities, providing valuable insight into the needs and interests of young people

Statistics reflecting the number of youth suffering from mental health, substance abuse, and co-occurring disorders highlight the necessity for schools, families, support staff, and communities to work together to develop targeted, coordinated, and comprehensive transition plans for young people with a history of mental health needs and/or substance abuse.

Nearly 30,000 youth aged out of foster care in Fiscal Year 2009, which represents nine percent of the young people involved in the foster care system that year. This transition can be challenging for youth, especially youth who have grown up in the child welfare system.

Research has demonstrated that as many as one in five children/youth have a diagnosable mental health disorder. Read about how coordination between public service agencies can improve treatment for these youth.

Civic engagement has the potential to empower young adults, increase their self-determination, and give them the skills and self-confidence they need to enter the workforce. Read about one youth’s experience in AmeriCorps National Civilian Community Corps (NCCC).