Youth who receive special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004) and especially young adults of transition age, should be involved in planning for life after high school as early as possible and no later than age 16. Transition services should stem from the individual youth’s needs and strengths, ensuring that planning takes into account his or her interests, preferences, and desires for the future.

Components of Positive School Climate

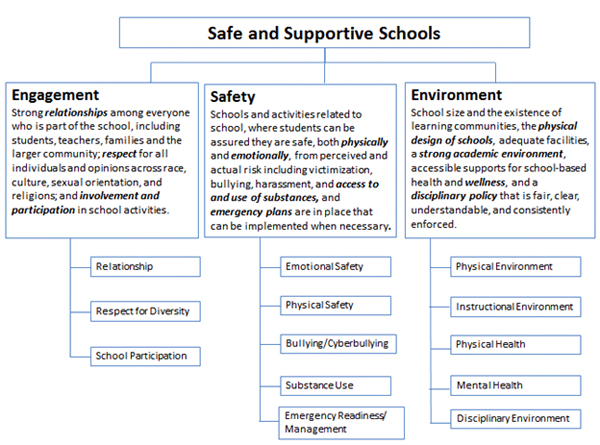

Although definitions of school climate vary, a comprehensive Safe Supportive Schools measurement model developed by the U.S. Department of Education, based on listening sessions and consultation with researchers and practitioners, reflects the most common concepts. This model includes three main components of school climate: Engagement, Safety, and Environment. The figure below1 illustrates an adapted version of this model—its components and topical areas under each—adapted from the website of the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (http://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/school-climate). For more information on the importance of school climate, view a recorded webinar.

School connectedness—students’ perceptions of safety, belonging, respect, and feeling cared for at school—appears to play a particularly important role in healthy adolescent development. It has been found to provide protection against almost every health risk behavior measured, including substance use, risky sexual behavior, violence, and emotional distress.2 Further, data on connectedness suggest that the more social domains in which adolescents experience connectedness, the less emotional distress and fewer symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress they will experience.3

Connectedness to school has also been shown to be a significant predictor of higher academic achievement among youth,4 including sexual minority youth.5 Analysis of data from the National Education Longitudinal Study shows that supportive, caring relationships between students and teachers, as well as teachers’ positive perceptions of students’ efforts in the classroom, resulted in higher academic achievement for students.6 Participation in extracurricular activities has been shown to be associated with positive academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes and civic engagement.7

The importance of relationships was also reflected in student, staff, and family data collected through the Safe and Supportive Schools (S3) state grants, which identified support for improving student-student, student-adult, and adult-adult relationships as the highest need across the participating local education agency sites in both 2011 and 2012.8 The positive effect of connection and relationships can also be seen among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students, who have been shown to be less likely to be truant from school if they have a trusted adult at school with whom they can talk about their sexuality.9 Learn more about what schools can do to help LGBT students.

Student safety includes feeling safe physically and emotionally from factors such as violence and teen dating violence, bullying and cyber bullying, and substance use. It also includes feeling safe as a result of emergency management plans in place. Students’ perceptions of feeling, or not feeling, safe at school have been shown to have an impact on their educational outcomes. School environments characterized by victimization and hostility are linked to lower levels of engagement and achievement in mathematics and reading,10 and personal experiences with threats, theft, or assault at school have been shown to increase students’ likelihood of dropping out.11 Negative outcomes are pronounced for students who are victims of bullying because these students have been shown to have lower academic achievement than their nonbullied peers. Victims of bullying, as well as bullies themselves, also report feeling unsafe at school at a higher rate than other students.12

Recent data show that students reported a higher level of fear of an attack or harm at school (4 percent) than off school property (2 percent) during the school year,13 and about 6 percent of students reported that they avoided school at least once during the previous month because they felt unsafe at or on their way to school.14 These feelings are often exacerbated for LGBT youth and youth with physical, intellectual, or developmental disabilities. These youth are more likely to face physical and emotional abuse, bullying, and physical assault because of their sexual identity, gender identity/expression, or disability.15 For example, data from a 2011 report show that 63.5 percent of LGBT youth felt unsafe from victimization at school because of their sexual orientation and 43.9 percent felt unsafe because of their gender expression.16

The use and sale of substances at school have also been linked to negative educational outcomes for students. A study conducted by the California Department of Education found that schools reporting a large percentage of students who stated they had been intoxicated or offered drugs on school property exhibited lower scores on academic achievement than other schools whose students did not report these experiences.17

The school environment includes a variety of factors such as the physical environment, instructional environment, student wellness, and discipline practices.

- Physical Environment: A well-maintained school environment has been shown to improve student achievement on standardized tests,18,19 and has been linked to increased teacher morale and commitment.20

- Violent incidents have been shown to repeatedly occur in the same physical spaces in schools. These locations, typically including lunchrooms, hallways, stairwells, and playgrounds, can often be characterized as “unowned,” public spaces that no one in the school feels a sense of responsibility to monitor.21 Identifying these hotspots, assigning adults in the school to monitor them, and reducing student presence in these areas, has been shown to decrease students’ perceptions of these spaces as dangerous.22

- Instructional Environment: Research has linked positive school environments to higher academic and behavioral outcomes for students,23 but in the 2007–2008 school year, 32 percent of teachers reported that student tardiness and class cutting interfered with their teaching, and 34 percent agreed or strongly agreed that student misbehavior interfered with their teaching.24 The implementation of classroom management strategies and practices can have a positive effect on decreasing problem behaviors, such as disruptions and aggression.25

- Mental Health and Well-Being: The Center for Mental Health in Schools estimates that between 12 and 22 percent of school-aged children and youth have a diagnosable mental health disorder.26 Young people with mental health problems have been shown to have lower academic achievement than their peers. Among these students, 14 percent achieve mostly Ds and Fs,27 and 44 percent drop out of school.28 School-based mental health programs can help reduce conduct disorder, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and depression symptoms in students receiving services.29 Learn more about school-based mental health and hear from young people about how school-based mental health services have helped them.

- Discipline: Punitive approaches to discipline such as zero tolerance, which embraces systematic suspension and expulsion, have been shown to lead to negative outcomes for youth. For example, data suggest that students who have been suspended are 30 percent more likely to drop out of school,30 be suspended again in the future,31 and perform poorly academically than their peers who have not been suspended.32 Disciplinary actions may be disproportionately delivered; research has shown that African American students and students with emotional disabilities are more likely to experience suspension and expulsion, which places them at higher risk for these negative outcomes.33 Conversely, proactive, schoolwide approaches to discipline have been associated with a decrease in discipline referrals and an increase in student attendance, academic performance,34 and achievement on standardized tests.35 Schoolwide approaches to discipline that focus on prevention reinforce a positive environment in which all students and staff are aware of behavioral expectations, which are enforced with predictability and monitored consistently.36

Resources

National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments

The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) is funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Safe and Healthy Students. NCSSLE provides resources, training, and technical assistance on school climate and its components to states, grantees, district administrators, schools, teachers and staff, families, and students. The NCSSLE website highlights the most up to date and seminal research on school climate and provides links to related products, tools, and websites.

StopBullying.gov

StopBullying.gov represents a multiagency federal effort to better understand the issue of bullying and how to prevent and respond to it. In addition to the resources provided for parents and other community members, StopBullying.gov features information to help schools educate students and staff about bullying and implement policies that create an environment of safety.

Office of Safe and Healthy Students

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Safe and Healthy Students (OSHS) funds and promotes initiatives, research, and publications on education, health, mental health, safety, and drug and violence prevention. The OSHS website provides an overview of the programs, initiatives, and technical assistance centers administered by OSHS and highlights relevant events, reports, websites, publications, and other available resources.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Adolescent and School Health: School ConnectednessThis webpage from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides a definition of and information on school connectedness and why it is so important.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Injury Center: School Violence

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Injury Center works to promote violence and injury prevention by gathering and reporting data, funding programs and prevention activities, and disseminating resources and tools. The School Violence topic page of the Injury Center provides statistics, risk and protective factors, and information about prevention efforts and tools related to school violence.

1 Adapted from Harper, 2010

2 Resnick et al., 1997

3 Libbey, Ireland, & Resnick, 2002; McGraw, Moore, Fuller, & Bates, 2008

4 Fredricks & Eccles, 2006

5 Seelman, Walls, Hazel, & Wisneski, 2012

6 Muller, 2001

7 Fredricks & Eccles, 2006

8 Child Trends & American Institutes for Research, 2012

9 Seelman et al., 2012

10 Ripski & Gregory, 2009

11 Neild, Stoner-Eby, & Furstenberg, 2002

12 Glew, Fan, Katon, Rivara, & Kernic, 2005

13 Robers, Kemp, Truman, & Snyder, 2013

14 Centers for Disease Control, 2012

15 Kosciw, Greytak, Diaz, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012; Stopbullying.gov, n.d.

16 Kosciw et al., 2012

17 California Department of Education, 2005

18 California Department of Education, 2005

19 Earthman, Cash, & Van Berkum, 1995

20 Cash, 1993

21 Corcoran, Walker, & White 1998

22 Astor, Meyer, & Behre, 1999

23 Brand, Felner, Shim, Seitsinger, & Dumas, 2003

24 Chapman, Laird, Ifill, & Kewal Ramani, 2011

25 Oliver, Wehby, & Reschly, 2011

26 Center for Mental Health in School, 2008

27 Blackorby, Chorost, Garza, & Guzman, 2003

28 Wagner, 2005

29 Hussey & Guo, 2003

30 Fabelo, Thompson, Plotkin, Carmichael, Marchbanks, & Booth, 2011

31 Tobin, Sugai, & Colvin, 1996

32 Mendez, 2003

33 Fabelo et al., 2011

34 Luiselli, Putnam, & Sunderland, 2002

35 Luiselli, Putnam, Handler, & Feinberg, 2005

36 Sprague, 2007

Youth Briefs

Research links early leadership with increased self-efficacy and suggests that leadership can help youth to develop decision making and interpersonal skills that support successes in the workforce and adulthood. In addition, young leaders tend to be more involved in their communities, and have lower dropout rates than their peers. Youth leaders also show considerable benefits for their communities, providing valuable insight into the needs and interests of young people

Statistics reflecting the number of youth suffering from mental health, substance abuse, and co-occurring disorders highlight the necessity for schools, families, support staff, and communities to work together to develop targeted, coordinated, and comprehensive transition plans for young people with a history of mental health needs and/or substance abuse.

Nearly 30,000 youth aged out of foster care in Fiscal Year 2009, which represents nine percent of the young people involved in the foster care system that year. This transition can be challenging for youth, especially youth who have grown up in the child welfare system.

Research has demonstrated that as many as one in five children/youth have a diagnosable mental health disorder. Read about how coordination between public service agencies can improve treatment for these youth.

Civic engagement has the potential to empower young adults, increase their self-determination, and give them the skills and self-confidence they need to enter the workforce. Read about one youth’s experience in AmeriCorps National Civilian Community Corps (NCCC).